Why Type 2 Diabetes Leads to Liver Damage for Some, Not Others

One the many unhealthy outcomes of America's state of obesity occurs when people start building up excess fat around their liver, a condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Obesity affects 42% of Americans. That high obesity rate is a major reason why an estimated 24% of Americans have developed NAFLD. Obesity also contributes strongly to the approximately 10% of Americans who have type 2 diabetes.

When people have both type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, they can have a sharply elevated risk of developing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a condition that goes beyond fatty liver to cause life-threatening liver inflammation and scarring. NASH also can trigger liver cancer.

However, this path toward severe liver damage is not automatic. Most people who have NAFLD never develop NASH, not even if they also have type 2 diabetes. Scientists have long suspected that genetic factors must play a role, but so far, few risk variants have been made clear.

Now a study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's and two research centers in Japan has tapped into the emerging power of organoid medicine to fill in some of the missing pieces. Their findings, which involved a novel method of producing liver organoids from multiple cell donors, may ultimately help doctors predict and treat the people most at-risk of NAFLD leading to severe complications. The study details were published online Oct. 13, 2022, in the journal Cell.

Learning from large numbers of human liver organoids

This work was led by principal investigator Takanori Takebe, MD, PhD, who holds research appointments in both Cincinnati and Japan. In recent years, Takebe's team has demonstrated the ability to mass produce human liver organoids. These tiny-but-functional mini organs are grown in the lab from human stem cells and can be customized to reflect specific disease conditions.

>>Recommended: What is Type 2 Diabetes? - Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

This study is among the earliest applications of the new organoid production technology for studying the causes of human disease at personalized and population level. The outcome: human data rather than animal data that reflects many—but not all—of the results researchers might learn from a clinical trial.

In this case, the research team grew liver organoids from the cells of 24 donors. To validate their usefulness as models for the disease, the behavior of these organoids were compared to data from more than 1,000 people with biopsy-proven NASH. (Watch a video abstract describing the process)

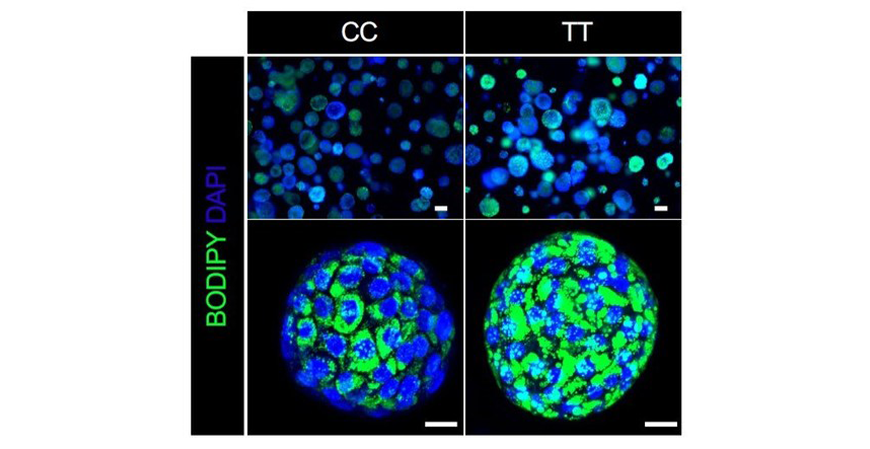

The team's experiments ultimately revealed that a single gene variant—GCKR-rs1260326 TT—acts as a dangerous double agent. When the liver is functioning in diabetic conditions (high glucose and high insulin levels), the presence of this variant sharply accelerates NAFLD fat accumulation. But when a liver is working within a healthy blood-sugar balance, that same variant actually helps prevent liver scarring more effectively than NASH livers that carry the normal gene.

"It is very exciting to be able to recapitulate genetically-determined individual's phenotype in an organoid model," says first author Masaki Kimura, PhD. " Our series of experiments using data from organoids and patients are further leveraged to disentangle the puzzling role of GCKR-rs1260326, revealing this variant exerts NASH protection and promotion depending on diabetes complications."

Implications for clinical care

The data from functioning human livers rapidly raised implications for clinical care.

For example, the team reports that metformin—a widely prescribed diabetes treatment—made liver organoid function even worse when the gene variant was present. However, replacing metformin with a combination of two drugs, nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nitazoxanide (NTZ), appears to stabilize the organoids' function.

This unexpected finding traces to changes the gene variant appears to cause in the liver cells' energy consumption rates. Metformin appears to further slow already weakened metabolic rates that occur when diabetes and NAFLD are combined.

In fact, the team matched this effect to HbA1c test results, which are routinely used to measure a person's overall diabetes control.

When the variant was present—and HbA1c values were within normal <5.7% ranges—several scores of liver function were better than those without the variant. In stark contrast, when HbA1c values were in the diabetic >6.4% range, the scores were much worse for the cohort carrying the variant.

>>Recommended: 5 Foods to Help Manage Your Blood Sugar

"We found that en masse population-based analysis under insulin insensitive conditions predicted key non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) factors, opening up a door for an array of future personalized medicine applications propelled by human organoids," Takebe says. "We also found, in collaboration with industry collaborators, that drugs that can uncouple oxidative mechanisms within cells helped improve mitochondrial function and may help livers adapt to the presence of increased fat. This suggests new potential ways to manage diabetic NASH."

About the study

In addition to Takebe and Kimura, co-authors from Cincinnati Children's included Takuma Iguchi, PhD, Kentaro Iwasawa, MD, PhD, Andrew Dunn, PhD, Wendy Thompson, PhD, Praneet Chaturvedi, MS, Aaron Zorn, PhD, Michelle Wintzinger, BS, Mattia Quattrocelli, PhD, Miki Watanabe-Chailland, PhD, Gaohui Zhu, MD, PhD, Masanobu Fujimoto, MD, PhD, Meenasri Kumbaji, MS, and Vivian Hwa, PhD.

The study included contributors from Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Yokohama City University, Gilead Sciences and The Liver Company, Inc.

This study was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, the Falk Transformational Awards Program, JST Moonshot R&D, the Takeda Science Foundation award, the Mitsubishi Foundation, and the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation.

- Log in to post comments